The Sultan of Sultans, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, al-Malik al-Ashraf, the powerful, the Dreadful, the Punisher of Rebels, Hunter of Franks and Tartars and Armenians, Snatcher of castles from the hands of Miscreants, Lord of the Two Seas, Guardian of the Two Pilgrim Sites, Khalil al-Salihi.

So began the announcement from the Mamluk sultan of Egypt to the Grand Master of the Knights Templar, informing him of his intention to stamp out the last enclave of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the city of Acre. This is the subject of The Accursed Tower, the latest book by Roger Crowley, whose other popular works are on seafaring, exploration, and great battles.

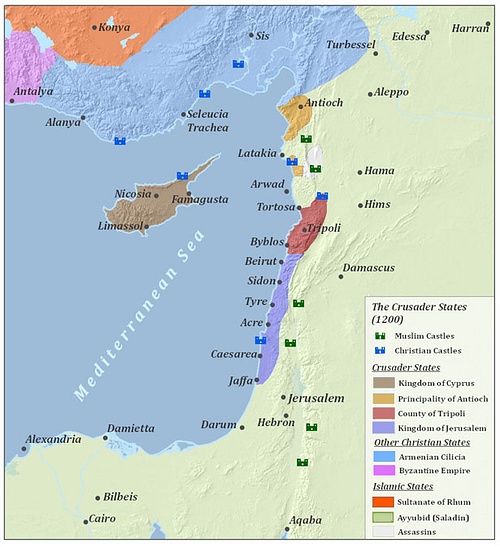

By the time of its conquest in 1291, Acre had been the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem for the previous hundred years, following the capture of Jerusalem itself by Saladin. In the intervening years, Saladin’s successors had whittled down the rest of the Crusader States until Acre was nearly all that remained. In this sense, The Accursed Tower somewhat resembles 1453, an earlier work by Crowley about the final fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans. Like the Byzantine Empire, the Kingdom of Jerusalem had long before been broken—the fall of their last great city was the dramatic realization of the inevitable. And like the nascent Ottoman state in 1453, the Mamluks’ conquest of Acre confirmed them as a great power, clinching their rule over Egypt and the entire eastern shore of the Mediterranean (Crowley was drawn to this subject in part because his last book, Conquerors, on the Portuguese exploration of the Indian Ocean (reviewed here), which involved a much later conflict between Europeans and Mamluks).

Acre, though no Constantinople, was impressive city in its own right. It housed up to 40,000 people within its walls and remained a major trade hub, connecting the interior of Syria to the wider Mediterranean world—it was in part a desire to eliminate this commercial competitor of Alexandria that prompted the Mamluks to move against it. Yet trade also complicates hostilities, as Venetian and Genoese merchants used the port city to transship the lumber, iron, and slaves that were critical for the Mamluk war effort.

When the sultan of Egypt finally resolved to reduce Acre in the spring of 1291, he brought a massive army that had been preparing for months. Crowley gives an excellent description of siege warfare, from the reconnaissance and preparation of the site, to the mining and battering of the walls, to the final assault through the breaches. The particularities of a medieval siege also remind us that there is nothing truly new under the sun in warfare: suppressive arrow and mangonel fire allowed assault troops to maneuver into position, and a final general assault on the walls masked the forces massed for the decisive breakthrough.

Crowley’s volume tells a compact and exciting narrative, characteristically full of interesting asides that also move the story along. He vividly relates the debauchery and factionalism of Acre, and how Muslim sultans used a massive and complex logistical apparatus to assemble large numbers of men and war machines before the city’s walls. In the broad sweep of history, the fall of Acre comes as something of an anti-climax, the final materialization of the inevitable end of the Crusader kingdom. Yet The Accursed Tower gives full life to the drama, allowing us to see it not as detached observers, but with the respective exhilaration and horror of all involved.