An ancient Chinese shipwreck in the Java Sea has been found to be much older than previously thought.

The new dating places it within a vast and intricate trading network that spanned from southern China to Egypt. The story of this ship and its cargo adds color to an already fascinating world.

A Major Haul

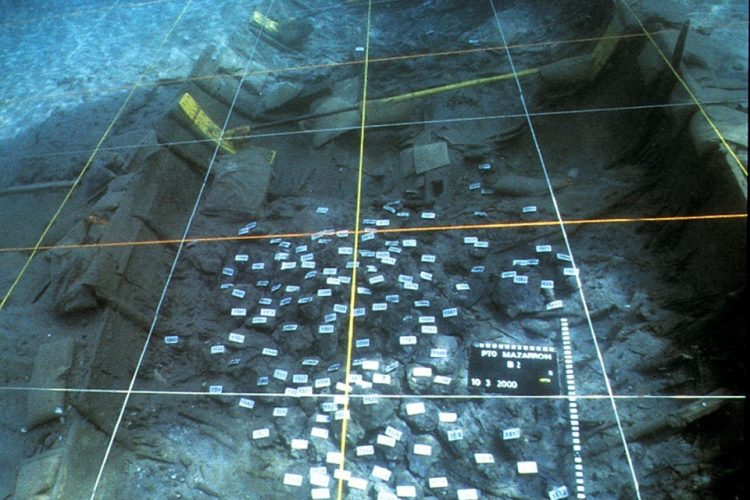

The wreck was found in the 1980s by fishermen off the Indonesian island of Sumatra. The ship itself had long since disappeared, but its cargo remained. This included 100,000 ceramic pieces, hundreds of tons of iron, as well as ivory, resin, glass and bronze objects, and tin ingots.

Radiocarbon dating done at the time showed the ivory and resin to be from the late 13th century. By this time, the Mongol Yuan dynasty under Kublai Khan had conquered southern China, until then ruled by the Southern Song dynasty.

The center of gravity of the Mongol Empire lay in the great Eurasian Steppe. Mongol rule made the Silk Road safe for merchants to travel, allowing them to reach Europe directly by land. The flow of trade shifted northward, far from the sea-lanes of Southeast Asia, causing a decline in maritime traffic.

Which is not to say that the Chinese shipwreck would have been completely out of the ordinary. History from the ground perspective is more continuous than the grand sweep of political events.

But it turned out there was more to the story.

Linguistic Clues

One small detail bothered one of the researchers:

The ship was carrying ceramics marked with an inscription that might indicate they were made in Jianning Fu, a government district in China. But after the invasion of the Mongols around 1278, the area was reclassified as Jianning Lu. The slight change in the name tipped [archaeologist Lisa] Niziolek and her colleagues off that the shipwreck may have occurred earlier than the late 1200s, as early as 1162.

This prompted further investigation. Samples were analyzed using more modern radiocarbon dating techniques. The results showed the shipwreck to be older than previously believed, as early as 1162.

The new date fits our understanding of Song-era maritime trade much better. What did this picture look like?

Portrait of a Voyage

The Chinese shipwreck leaves many clues as to where the ship had been and where it was going. It tells a fascinating story, not just of the voyage itself but of the world in which it took place.

Fortunately, we have a rich backdrop in which to place this voyage. This is in large part thanks to the work of a contemporary Song official.

The Zhu Fan Zhi

The port of Quanzhou, a likely point of origin for the ship, was by then the biggest in Song China. It was a major emporium for Chinese exports and imports from around the world.

There lived in Quanzhou at the time a man named Zhao Rugua, who was a supervisor of maritime trade. He spoke with many merchants and sailors in the course of his duties, and often asked them about their travels. After many years of this, he compiled their stories into an extensive account of foreign lands, called the Zhu Fan Zhi. This detailed the peoples who lived there and the goods they produced (and can be read online here).

The Zhu Fan Zhi is a snapshot of Asian commerce at the exact time of the Chinese shipwreck. The items salvaged from the wreck both confirm its account and are illuminated by it. So what does it tell us?

Home Port: China

At least two of the commodities on board were of Chinese origin: the iron and most of the ceramics. Then, as now, China was a major manufacturer and exporter. Iron, which could be used to make weapons, was in particularly high demand in neighboring countries.

We already know that some of the ceramics came from Jianning. According to Marco Polo, who visited sometime after the Mongol conquest, it was a sizable town that produced silk, cotton, and spices. This testimony, along with the ceramics discovered in the Java Sea wreck, suggests a heavily export-oriented economy.

The ceramics were likely shipped downriver to a seaport on coast. Quanzhou is cited by scholars as the most likely port of origin for the voyage, but the smaller Fuzhou, a hundred miles north, is also a candidate. It lies on the mouth of the same river system as Jianning, making it a possible port of embarkation for the pottery.

Once it reached a port, the wares would have been purchased by merchants looking to ship them abroad. How did they do this?

Sharing the Risk

Financing trade expeditions, as with financing ships, is risky. A lot of capital is tied up for an extended period, with the chance of losing it all at once. It was very common at that time for investors in southern China’s coastal cities to pool cash to finance expeditions.

In a pattern repeated across time and place, each individual would be responsible for only a fraction of the total capital required. This also allowed them to invest in several simultaneous expeditions, reducing overall risk. The return on each was several times the initial investment, making Southeast Asian trade very lucrative for merchants who knew what they were doing.

Setting Sail

What of the ship itself?

The Chinese shipwreck was probably not a Chinese ship. Residue from the decayed hull reveals it was a type of hardwood native to Southeast Asia. No metal fastenings were found, suggesting the boards were lashed together. All this is characteristic of ships made in Java or Sumatra.

The distribution of the cargo on the seafloor allowed researchers to estimate the size of the boat: about 90 ft long and 25 ft wide. This means it would have been a fairly sizable junk, or djong, as the Javanese variety was called. Nevertheless, there is reason to believe that the home port was in China, as we shall see.

Down the Coast

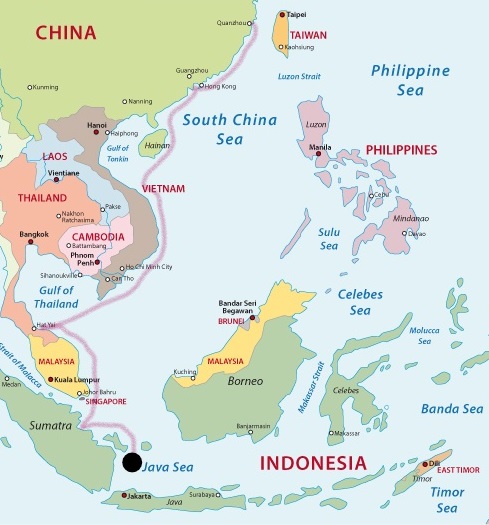

Junks of the time tended to sail close to shore, either hugging the coastline or hopping from island to island. The South China Sea is ringed by the mainland and archipelagos, but is mostly empty of islands in the center. This means a ship departing southern China could take a clockwise or counter-clockwise route. The cargo again provides hints.

First, the iron. There is no certainty as to where the iron it was picked up—it could very well have been loaded at the home port.

Another likely possibility is Guangzhou (formerly known as Canton), which lies to the southwest of the Chinese coast. This had been the biggest port in southern China, and was surpassed around this time by Quanzhou. A large volume of iron for export flowed through here, making it a likely stop. From there, it is easy to follow the Vietnamese coast south.

Next, the pottery: not all of what was on board was Chinese. Some were fine earthenware pieces called kendis. These are distinctive to the small region of Patani, on the Malay peninsula in the modern southern Thailand. These may have contained crew’s provisions, or were used to store some other commodity. Whatever the case, the ship likely picked them up on a stop in Patani en route to Sumatra.

All of this suggests a westerly path for the ship. After these initial exchanges, it was on to the islands of the Malay Archipelago.

Srivijaya: Portal to a Wider World

The sheer number of islands and countries in Southeast Asia, easily accessible by sea, each producing unique natural and manufactured goods, made commerce boom. It was only natural that states in the region tended to form around either control of resources or control of trade routes.

Among the latter type was the empire of Srivijaya. Centered on the island of Sumatra in modern Indonesia, it had been flourishing for centuries by the time of the shipwreck.

Although modern historians call it an empire, Srivijaya was more a confederacy of tributary kingdoms. It was extremely powerful nevertheless, dominating all of Sumatra, much of the Malay Peninsula, western Java, and numerous smaller islands.

This gave Srivijaya control of the Strait of Malacca, and hence of all sea traffic between the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. Ships came seasonally from India, carried across the Bay of Bengal by monsoon winds. They would sell goods from as far afield as Europe in Srivijayan ports, to be transshipped thence across the Far East.

Sumatran Goods

Sumatra itself was a major source of export goods. Lush jungles furnished a wide variety of precious commodities, including spices, hardwoods, resins, ivory, and precious metals.

The ports of Sumatra teemed with exotic goods, whether gathered from the interior or shipped from elsewhere. Our djong almost certainly stopped in one of them, where it unloaded Chinese manufactures, perhaps to include silk, to be shipped west. The Zhu Fan Zhi tells us that this was one place where Chinese merchants purchased both ivory and resin.

But that does not tell us where the ivory and resin on the Chinese shipwreck came from. The Srivijaya Empire produced and transshipped varieties of both, making their origins tricky to confirm. Age and exposure to salt water made the resin particularly difficult identify. Spectral analysis found it was most likely Indian, or perhaps a type of Sumatran green amber.

Research to determine the origin of the ivory is ongoing. There are several possibilities, however.

The first is that the ivory was Asian in origin. The Zhu Fan Zhi records elephants living in an area stretching from Vietnam down to Java. Asian ivory would have been available in either Sumatra or Patani, the former having a greater abundance.

Another strong possibility is that the ivory came from Africa. By this period, Arab and Persian merchants had been shipping elephant tusks across the Indian Ocean for centuries. They purchased them from ivory merchants on Zanzibar, which was part of a very active East African trade.

African ivory commanded a premium over Indian and Southeast Asian varieties, which were brittle and difficult to carve. Song dynasty China saw a growth in ivory carving, with techniques becoming ever more sophisticated and demand ever greater.

Whatever the case, both resins and ivory were highly sought-after in China. The Sumatran ports that carried them would have been highly trafficked by Chinese vessels of all sorts, including our djong.

Final Stop?

The djong appeared to be on its way to Java. The iron and ceramics found in the Chinese shipwreck were still unsold. These would be traded for spices—most likely pepper—as well as local delicacies. The iron especially would have commanded a high price: several squabbling kingdoms existed on Java at the time, and they all needed material for weapons.

After a stop on Java, the bulk of the ship’s cargo—resin, ivory, and spices—would be goods for the Chinese market. Unless the merchants intended to continue on to the Spice Islands, this would be the only point in the voyage where all merchandise on board was intended for a single destination. The ship could therefore end its voyage in the same port it began, selling its entire cargo and paying out its investors before setting off again.

The ship never reached Java, however. It sank under the waves some distance off the Sumatran coast, to be preserved on the seafloor until the modern day.

The Chinese Shipwreck As A Thread in the Tapestry

Trade networks are as a messy spaghetti tangle when looked at from the human level. But out of the chaos and din of wharfside commerce, certain patterns emerge in a broader perspective.

During this time in particular, the whole of Eurasia and Africa consisted of interlinked zones of trade. Seas and landmasses composed these zones, wherein neighboring countries carried on particularly intense commerce.

The coasts and islands of Southeast Asia formed one such zone. The countries surrounding the Bay of Bengal were another. The Arabian Sea littoral yet a third. Each zone overlapped with its neighbors, like a Venn diagram of many spheres. Together, they created a vast and intricate network of trade that allowed goods to flow between the Far East to Western Europe without direct contact.

The Chinese shipwreck gives us a small window into that world. The ship, traveling a modest circular itinerary, carried goods from several different lands located thousands of miles apart.

Glimpses such as these are rare and fleeting, but incredibly tantalizing. Taken altogether, they form a vivid and detailed picture of this incredible world, which only more research and exploration can fill out.