The previous post in the Fall of Byzantium series is here.

John Cantacuzenus was at his headquarters in Thrace when he heard the news that he had been stripped him of his titles and declared an outlaw. A stream refugees arrived soon after from Constantinople, bringing stories of the depredations committed against anyone even suspected of supporting the Grand Domestic. An anxious foreboding filled the fortress-city of Didymoteichon.

The army reacted with outrage. Instead of returning to the capital as ordered by the regency, they acclaimed Cantacuzenus emperor—for all of John’s political enemies, he was well-loved by the troops. This put him in a difficult position though. The throne was an honor that he had refused several times in the past, when Andronicus had tried to make him co-emperor and when Apocaucus had urged him to seize it. His claim to a legitimate role in the government was justified by his position as regent; he therefore had to be careful to uphold the rights of John Palaeologus and specify that his complaint lay with the regency.

But John had few allies, and there was no sense in disappointing the ones he did have. He therefore consented to be invested emperor at a ceremony in Didymoteichon. Empress Anna and Emperor John V’s names were acclaimed before Cantacuzenus’ own, making it clear that he was not trying to usurp his co-emperor’s inheritance.

A Rent in the Fabric

The regency promptly responded by excommunicating Cantacuzenus and having John Palaeologus formally crowned. Now began the propaganda war: the partisans of Cantacuzenus had the proclamation of his elevation read out in nearby cities, including Adrianople, the largest city in Thrace. The reaction there was mixed: the aristocrats reacted joyfully, while the lower orders were more muted. The allies of the regency gave the artisans and men of the market a pole around which to rally, and overnight sullen silence turned to angry protest. The very next day, clamor turned into a mob and all the supporters of Cantacuzenus were driven out of town.

Similar scenes were repeated in cities across the empire. If it appeared that Byzantium was witnessing a social revolution, this was largely at the instigation of regency agents. Alexius Apocaucus in particular, himself of humble origin, whipped up crowds against the pretender, using him as the object for every resentment (an act of singular ingratitude toward the one man who had recognized Alexius’ talents and helped lift him up). The charge of “Cantecuzenism” soon became a general-purpose term of abuse.

All of which is not to say that the mob did not have legitimate grievances. The constant campaigning of Andronicus III had cost a lot of money, the burden of which fell most heavily on the lower orders. Whether powerful lords managed to evade taxes or were simply cushioned by their enormous wealth, they did not experience the suffering of the peasants. Cantacuzenus was particularly vulnerable to this charge. He owned enormous estates in every part of the empire, and was one of the empire’s largest landowners.

Reasons of self-preservation aside, it became clear to Cantacuzenus that the regency must be stopped. They were recklessly tearing apart the empire as a means of consolidating power. Could this be done without making the situation still worse?

Opening Maneuvers

No sooner had civil war broken out than the early onset of winter restricted maneuvers to the diplomatic field. Anxious months passed as envoys struggled back and forth over the snowy roads between Didymoteichon and Constantinople. Even now, Cantacuzenus held out hope that open warfare could be averted. The empress evidently began to express second thoughts about the whole thing: Cantacuzenus had, after all, always loyal to her late husband, and his scrupulous attention to protocol during his coronation showed that he was not contesting her son’s rights. This line of thought was firmly rejected by the patriarch and Alexius, however, and they turned away multiple envoys sent from Didymoteichon.

Diplomacy having failed, John had no choice but to fight. The question was how: although a large part of the army was loyal to him, the regency had swiftly taken control of the major cities of the empire. Fortresses being essential to controlling regions in medieval warfare, this put John at a great disadvantage. One large opportunity did present itself: an old ally, the governor of Thessalonica, offered to turn the city over to him. Thessalonica was a major center, the second city of the empire and a large port. Controlling it would give John legitimacy and allow him to contact allies in Epirus and Thessaly. As soon as the weather improved in early 1342, Cantacuzenus headed off with a small force to claim the city.

Too late. Alexius beat him to the punch by sending a squadron from Constantinople, which pulled into harbor just days before Cantacuzenus arrived. The Thessalonican mob had meanwhile forced the aristocratic faction out of town and set up a popular government, which came to be called the Zealots. Alexius, like a man jumping in front of a parade and declaring himself its leader, claimed this as a victory. He was satisfied to have denied an important city to his enemy, at whatever cost to the empire. The Zealots’ destructive and horrific reign would last eight years, longer than the civil war itself, showing what unruly forces the regency had unleashed.

Even worse news soon reached John: an army from Constantinople was laying siege to Didymoteichon. Shut out of Thessalonica and cut off from his base in Thrace, he was stranded with only a small force in the mountains of Macedonia. John needed allies, and fast.

The Dilemma

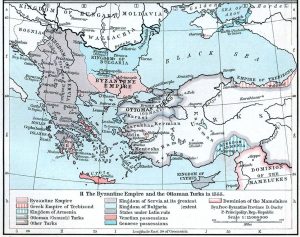

John was now in an extremely difficult position. It was still early in the season, which meant food and fodder were scarce, especially up in the mountains. He was also close to Serbian territory. The Serbs had become the great regional power within the last century, having shaken of their vassalage to Byzantium and become an independent kingdom. They expanded quickly in all directions through the Balkans, including many towns and fortresses once held by Byzantium.

All the more dangerous for the empire was Serbia’s ruler, an ambitious, young king named Stefan Dušan. He had already done much: he won territory in northern Macedonia from Andronicus III and used ruthless diplomacy to become the senior partner in an alliance with Bulgaria, traditionally Byzantium’s greatest enemy. Dušan’s youth meant that he was still tested by his own nobility, which meant he needed to prove his strength through conquest. Serbia loomed over Byzantium like a bank of dark clouds.

At the same time, Serbia was Byzantium’s only hope. What other power was on hand to help Cantacuzenus in his most desperate hour of need? John traveled deep into Serbian territory to meet with Dušan and test the waters. It is unclear exactly what terms Dušan offered, although it very likely included a sizable territorial concession. A dangerous precedent had been set in the civil war Andronicus III fought against his grandfather, when outside powers got involved in a Byzantine civil war for their own gain—whatever Dušan offered, he clearly expected to profit from it. John had an eye on the long-term throughout the course of the war, and was not simply willing to throw territory for short-term gain. Both he and the regency were weak compared to the might of Serbia, so inviting them into the war could be a disastrous mistake. John did after all have sympathizers in Thessaly and Epirus. Could he not enlist them in his war effort?

There were several problems with that, the first being how to get them. The route into Thessaly was blocked by regency-held fortresses; he might get stuck in Macedonia as he had while trying to reach Thrace. Next was the fact that his sympathizers had not yet openly declared for him. Supposing they did, the regency would do everything in its power to subvert them, and the experience of Thessalonica might repeat itself. Time was also a factor. No one knew how much longer Didymoteichon could hold out, and if it fell, John was lost. Building up support in the west would take time, but his supporters in Thrace needed help now.

Neither of the options were good, but a decision had to be made: John made a deal with Dušan.

Dark Days

This did not immediately improve the situation. John and his reinforced army twice tried to break out of Macedonia into Thrace, but were blocked both times by a thicket of regency-held fortresses. Trapped in the mountainous wilderness and afflicted with disease, many of John’s troops deserted. The rest of the army returned to Serbia; John’s supporters in Didymoteichon would have to hold out as best they could. But bad news soon arrived: the regency had enlisted Bulgarian troops, who were ravaging the area around the city.

Complete disaster was only averted with the help of John’s old friend Umur, Bey of Aydin, a small Turkish state on the west coast of Anatolia. John had befriended Umur under Andronicus III, when the Turk lent him troops for his campaigns in the Balkans. The bey came through yet again, sending a large force to beat back the Bulgarians and relieve the pressure on Didymoteichon. He then tried to link up with John, but the arrival of winter closed the mountain passes into Serbia, forcing him to return home.

Cantacuzenus began the campaign season of 1343 on a different tack. Over the past year, nobles from Epirus and Thessaly had declared for him, and he now wanted to bring those regions under his control. He therefore headed west with some Serbian troops and succeeded in capturing key fortresses on the border between Macedonia and Thessaly. With a continuous belt of territory in his possession, John now made a second attempt on Thessalonica.

Fortune was finally beginning to swing in Cantacuzenus’ favor, so Stefan Dušan did what mercenaries often do in such cases: he switched sides. The Serbian king realized there was more profit in prolonging the conflict than in helping the winner, so he recalled the troops he had loaned to Cantacuzenus. Dušan would spend the rest of the war conquering Epirus and Macedonia, leaving John surrounded by enemies on all sides. When things appeared as if they could not get any worse, a fleet arrived from Constantinople to reinforce the Zealots. There was no hope of taking Thessalonica; John was trapped.

Turning of the Tide

At this most desperate hour, Cantacuzenus was saved once again by Umur Bey, who arrived by sea with a large force. Thessalonica was too strong to be taken even with reinforcements, so the two friends marched east, breaking through the regency’s defenses in eastern Macedonia and finally reaching Didymoteichon.

No longer in immediate peril, John held a favorable position. Having largely abandoned western Greece to its fate, he was free to maneuver and consolidate his hold on Thrace. The next few years would be a drawn-out war of attrition in which, one by one, towns and fortresses came over to his side. Meanwhile, the regency was falling apart. There was hunger and discontent in the capital, making the regency very unpopular. Many high officials defected to the Cantacuzenus camp, including Alexius Apocaucus’ own son. In 1345, Alexius was killed in an uprising of political prisoners, victims of the regency’s increasingly harsh crackdowns.

The balance had shifted decisively in John’s favor, but at what cost? Turks and Bulgarians lived off the fat of the land at Byzantine peasants’ expense. Stefan Dušan controlled nearly everything west of Thrace. Having torn itself apart, the Byzantine Empire was now being devoured by external enemies. John controlled the bloody stump remaining to the empire outside of Constantinople, but even now the regency refused to negotiate. It was clear that Cantacuzenus would have to deliver the finishing blow, so in February 1347, he sneaked into the capital with a small force and surrounded the imperial palace. At last, the war was over.