Before the Spanish Reconquista began making serious gains, and before the First Crusade was launched for Jerusalem, there was another counteroffensive fought by the forces of Christendom against Islam. This first reconquista was of the rich island of Muslim Sicily.

The island had been in Muslim hands since the early 10th century, when the armies of a North African emir completed its conquest. Sicily was a large and rich prize that safeguarded Muslim sea traffic between the eastern and western Mediterranean, and served as a base for offensive operations against Christian states.

Economically and militarily, Sicily was an important objective in a larger struggle taking place across the Mediterranean world. Was it also the opening round in a wider holy war?

The Era of Christian Holy War

Historians often date the beginning of the religious dimension of the Spanish Reconquista to the mid-11th century—specifically, to the so-called Crusade of Barbastro, a 1064 expedition against an important fortress in northern Spain. For the first time in that era, the pope gave explicit religious justification for a military campaign against the Muslim world. He set about recruiting knights from across Europe to go fight, exhorting them to take pity on their fellow Christians in Spain.

But just a few years before that, the Pope had authorized the Norman ruler of southern Italy to reconquer Muslim Sicily. It was his prerogative, enshrined in the (forged) Donation of Constantine, to invest princes in the lands that had been the western Roman Empire. He accordingly chose one of the greatest generals of the age, Robert Guiscard, to wrest the island back from the Muslims. This set the pattern for the reconquest of Spain and Crusades to the Holy Land, which would dominate the next two centuries.

But before looking at the reconquest of Muslim Sicily itself, it is worth understanding the broader context.

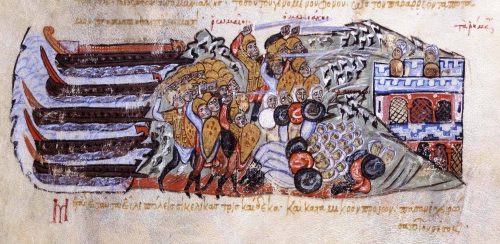

The War at Sea

The explosion of Muslim armies out of the Arabian peninsula following the death of Mohammed brought enormous swathes of the Mediterranean under Islamic control. Within a century, Muslims had conquered all the coasts from Spain to Syria. Only the north coast remained under Christian control; the sea looked likely to turn into a Muslim lake.

During this time, the Arab navy also made serious attempts to capture the major islands. Cyprus, Rhodes, Crete, Sardinia, and Corsica were all invaded, and partially or wholly occupied for brief periods. But the Arab navy was never strong enough to fend off counterattacks or guarantee the resupply of fresh troops and provisions. Inevitably, any island territory seized would be lost after a short period.

Of all the major islands in the Mediterranean, Sicily was the biggest and most significant. It remained a bulwark of Byzantium, neatly splitting the sea into eastern and western halves. If the forces of Islam were truly to control the Mediterranean, this would be an important objective.

The Muslim conquest of Sicily began later and took longer than the invasion of Spain. Within ten years of crossing the Strait of Gibraltar in 711, the Moors had already reached their maximum territorial extent on the Iberian Peninsula and were pushing into southern France. The conquest of Sicily, by contrast, did not begin until a full two centuries after the death of the prophet, and took 75 years to complete. Why was this?

A Sea-Washed Bastion

Unlike the vast deserts of North Africa, where Arabs had a natural fighting advantage, or the divided and fractious Gothic kingdom of Spain, Sicily was a well-defended and defensible island. It was separated by several hundred miles from the North African coast, with only a few small, barren islands lying in between.

Throughout the 8th century, Arab seamen had carried out many plundering raids from North Africa, and even briefly secured the tribute of Syracuse. But the Byzantine garrison was too strong, and the population too loyal, for them to have more than fleeting success.

It comes as no surprise, then, that treason, more than force, delivered Sicily into Muslim hands. So it happened that a turncoat Byzantine admiral arrived in North Africa with an intriguing proposal.

The Founding of Muslim Sicily

The admiral was named Euphemius, and in 826 he had recently fallen from grace. He fled Sicily with his ships and men for Ifriqiya, a semi-independent emirate in what is now Tunisia and eastern Libya. There he made a proposal to the ruling emir, Ziyadat Allah: Euphemius’ ships would help a Muslim army to conquer Sicily, and in turn he would rule the island as the emir’s vassal.

Ziyadat Allah realized he had a prime opportunity. Not only was this man offering his services, but discontent among high-ranking military commanders would mean morale was low among the defenders. Ziyadat accepted, and the following year sent a force to conquer the island.

Euphemius was killed early on, freeing Ziyadat to name a cousin as governor. This would keep Muslim Sicily closely bound to the rulers of Ifriqiya in the future. Byzantine resistance was stronger than anticipated, however, and fighting stretched out for several decades. Reinforcements from Constantinople and internal dissension among the Muslims interrupted their progress. Nevertheless, they captured Palermo in 831, and another major city every decade or two thereafter. The last major citadel fell in 902, finally ending Byzantine rule.

The conquest had lasted 75 years in all; in little over twice that, the reconquest would begin.

Life in Muslim Sicily

How did life change for Sicilians under Muslim rule?

The pattern was similar to Spain. There was an indifferent tolerance in the early years that allowed Christians to quietly practice their faith so long as they submitted to a restriction of rights and paid the tax on unbelievers. Over time, as civil and religious authorities became firmly entrenched, Muslim bigotry grew more overt. Oppression of the Christian population drove it to revolt several times, which was met with fierce retribution and further restrictions of liberties.

Despite this narrow-minded aspect of Islamic rule, the island grew in some ways more cosmopolitan. Sicily had been something of a backwater under Byzantium, lying at the furthest reaches of the empire. Muslim Sicily was much more central to the Islamic world: it enjoyed easy communication with the friendly ports of Syria, Egypt, Spain, and North Africa.

The island’s governor transferred the capital to Palermo and undertook a major building program there. Palaces, mosques, baths, and public buildings were erected to make the city worthy of a great kingdom. The population swelled as Palermo drew people from all over, soon making it one of the largest cities in the Mediterranean.

Scholars and poets were among the new arrivals, adorning the court with their presence. The Muslim world of this time was composed of many different princely seats that competed for prestige, and patronizing men of letters was a natural extension of this competition. Palermo soon began to rival Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, and Cordoba.

Which is not to say that the effects of Muslim rule were purely urban in nature. The Arabs introduced new crops and irrigation techniques, turning the island into a major producer of pistachios, citrus, sugarcane, and cotton. These cash crops were exported to all the major ports of the Mediterranean.

A Change of Power

It was a turbulent time in the wider Muslim world. Political power shifted rapidly, and borders transformed as states were created and dissolved. Ifriqiya was conquered in 909 by a new dynasty, the Fatimids. They managed to gain control of Sicily as well, and would go on to conquer Egypt.

The Fatimids were adherents of an austere form of Shi’a Islam called Ismailism (the same sect as the Assassins). This put them at odds with the Sunnis of Ifriqiya and Sicily, and introduced a new element of religious tension. Revolts broke out both in both parts of Fatimid territory, throwing the region into a period of chaos. The Greeks living in the eastern part of the island raised their own flag of rebellion, and invited Byzantine forces in Italy to help them throw off the Arab yoke.

After a half-century of Sunni and Christian revolts against heavy-handed Shi’ite rule, the Fatimids installed a governor, al-Hassan al-Kalbi, who managed to take firm control of the island. Not long after, the Fatimids conquered Egypt and moved their capital to Cairo. Sicily was a more distant consideration, and al-Kalbi’s descendents were free to rule semi-autonomously for the next century. But behind the smooth facade of the court were fractious squabbles that would ultimately lead to the end of Muslim Sicily.

The Christian Counteroffensive

From the mid-10th century onward, there was a belated pushback against Islamic expansionism. All across the Mediterranean, Christian powers began retaking territories they had lost in the past few centuries.

The efforts began in the east. Byzantium benefited from a succession of long-reigning soldier-emperors who managed to push back enemies on all sides, recovering territory and expanding their borders. Major gains were made in Anatolia and Syria at the expense of Muslim emirs.

In the west, this took place largely on the littorals. Pirates were expelled from their nest in southern France. Genoa, recovering from complete destruction by Arab pirates in 934, and Pisa, which also suffered devastating raids, began undertaking retaliatory expeditions. They started by clearing out bases on Corsica and Sardinia, and eventually went on to raid Ifriqiya itself.

Warriors from the North

Soon Muslim Sicily would be targeted. But as with the Spanish Reconquista and the Crusades, the reconquest of Sicily was spearheaded by warriors from northern Europe. In this case, they were not zealous Christian warriors, but mercenaries lured south by the promise of lands and booty.

Beginning in the early 11th century, disinherited younger sons and adventurers began migrating from Normandy to seek their fortune in southern Italy. Landless and penniless, they found work as mercenaries in service to the various powers of the region, the strongest of which was Byzantium.

The Normans played a weak hand well, exploiting local rivalries to improve their own position. Different bands fought for different powers, so when one side was defeated and captured, their victorious compatriots were able to secure easy terms of release. The Byzantines were impressed by their fighting skill, and became their biggest employer.

Prominent among the Normans were the brothers Hauteville, eight in all, who trickled down to southern Italy over the course of decades. These men were remarkable warriors and natural leaders, qualities which quickly won them positions of high command among their countrymen. Two of them would go on to lead the conquest of Muslim Sicily. But it was during those early years of mercenary service that the Hautevilles got their first taste of the island’s wealth.

Constantinople’s Sicilian Expedition

The year was 1038, and the Byzantine Empire was at its height. Over the past century it had systematically broken the strength of several powerful enemies, and expanded their borders by hundreds of miles to recover lost territory. The treasury was full, the frontiers were secure, and the army was strong.

The time was now ripe for a bid to bring Sicily back into the empire. The prospects were hopeful: success would put an end to the Muslim pirate raids on Byzantine Italy, and would bring in a great source of revenue. A large army was sent from the empire’s eastern provinces to Italy, where the commanders set about raising auxiliaries. The Normans were always eager for battle and loot, and so a corps of several hundred knights joined the army. Among its leaders was one William de Hauteville, accompanied by two of his younger brothers.

The force crossed the Straits of Messina, and met with initial success. But after two years, the expedition fell apart from factional squabbles. First, the Normans abandoned the enterprise. They punched far above their weight and were crucial to several victories, but felt they received an inferior share of the spoils. Then a conflict between the Byzantine general and admiral caused the former to be recalled to Constantinople, dooming any chance of victory.

The Byzantine failure presaged eventual Norman success. The debacle had embittered William and his brothers against Byzantium. Henceforth, they would no longer be loyal servants to Constantinople, but would strive to make themselves masters of Byzantine territory. The misadventure also showed them what a prize Sicily was, vulnerable and rich. The plucking of the fruit would have to wait, however, until such a time that the ambition and cunning of an Hauteville could wield the full forces of southern Italy.

Masters of Apulia and Calabria

After their unhappy experience in Sicily, the Hauteville brothers and several other leading Normans returned to Italy to plan their next moves. Opportunity presented itself when some local barons invited them to join a revolt against Byzantine rule. Victory in battle allowed the Normans to carve out a fief for themselves in the mountainous interior. William was elected Count of the Normans of Apulia and Calabria, and as-yet-unconquered lands were divvied up among the leading men to be wrested from Byzantium.

Around this time, two of the younger Hauteville brothers arrived from Normandy: Robert, nicknamed “Guiscard” (“cunning”), and Roger. Robert was a force of nature, and quickly proved his worth to his older brothers. He achieved such prominence, that a decade after arriving in the south, he became the fourth Hauteville brother to be elected Count.

Two years later, in 1059, the pope formally invested Robert as Duke of Apulia and Calabria and Duke of Sicily. But much of Apulia and Calabria was not yet in Norman hands; the pope had effectively given Robert sanction to conquer the remaining Byzantine lands in Italy, before moving on to Sicily.

The Reconquista Begins

From the papacy’s perspective, the conquest of Muslim Sicily would serve several purposes. First and foremost, it would eliminate a dangerous enemy of Rome. Sicily was the nearest base for the Muslim sea-raiders that had long plagued Christian lands in the western Mediterranean. Arab corsairs had sacked St. Peter’s in 846, and even occupied part of Apulia for several decades.

Second, it expanded the influence of Rome within Christendom itself. A long-brewing conflict between eastern and western divisions of the Church was reaching a head around this time. The Greek Patriarch in Constantinople resented papal claims to primacy over all Christendom, and had theological quibbles of his own with the Latin rite. By investing Robert Guiscard as duke of Sicily, the pope was asserting his power in what had long been Constaninople’s purview.

Third, it kept a dangerous neighbor occupied. The Normans had shown themselves to be unpredictable and uncontrollable during their time in southern Italy. They had gotten so powerful in such a short period that in 1053 the Pope raised an army to expel them from Italy. The Normans were victorious, and even managed capture the Pope himself.

In an unexpected turn, the Normans saw the long-term wisdom of an alliance with the Pope, and so swore him fealty and set him free. This did nothing to diminish the concrete power they had acquired, while it lay the groundwork for a mutually-beneficial alliance. The fruits of this were that the Normans would henceforth act as faithful protectors to the Pope, who in turn would legitimize their existing and future conquests.

Invasion

Before Robert could start in on his conquest of Sicily, he had to realize his claim to Calabria. The next two years were spent rolling up Byzantine possessions down the length of the Calabrian peninsula. By 1061, Robert and Roger were masters of the province, and had gathered a large force in Reggio. They crossed the straits and quickly captured Messina, going on to capture several surrounding fortresses. Robert soon returned to deal with affairs on the mainland, leaving his brother to carry on the conquest.

Roger won a major victory at the Battle of Cerami in 1063 that halted a Muslim counteroffensive and secured Norman gains in the northeast. He would continue to make progress on the island, periodically reinforced by his elder brother. Robert returned for an unsuccessful siege of Palermo in 1064, and for a successful one in 1071

The Reconquista Becomes a Holy War

These early successes in Sicily were followed by an escalation of events in Spain. The same year as Roger’s great victory at Cerami, the pope decried the perilous state of Spanish Christians. He appealed to Christian warriors from across Europe to help their brothers in need, thereby launching the so-called Crusade of Barbastro. This was the first explicitly religious sanction given by the papacy to a military expedition in Spain. But following as closely as it did on heels of the Norman expedition against Muslim Sicily, was there not already a precedent set?

Interestingly, a contingent of Italian Normans went to fight at Barbastro. Perhaps inspired by their comrades in Sicily, they answered the pope’s call to fight Islam in Spain. This is no indication of an official Church policy, but could suggest an existing “Crusading spirit,” which would a generation later inspire tens of thousands of warriors to set off for the Holy Land.

There is another aspect to be considered. Up until the Norman conquest, the Byzantines had been de facto protectors of all Christians in Sicily. They were the last Christian power to rule the island, and had maintained close contacts with the its Christian population throughout the Muslim occupation, launching several expeditions to liberate their coreligionists.

The success of the Normans put an end to this, and allowed the Church of Rome to assume authority over Greek Christians in southern Italy. With Latin Christendom directly abutting Muslim Sicily, the papacy took a new concern for Christians living under Islamic rule. The new holy struggle envisaged not just taking back land from Muslims, but winning over the faithful from the Byzantine rite. This dynamic would play out during the Crusades, as western Europeans conquered once-Byzantine lands from the Muslims.

The End of Muslim Sicily and Beginning of the Norman Kingdom

The Normans under Roger de Hauteville continued to take territory, and they seized the last fortress of Muslim Sicily in 1091. Not long after, the pope raised the combined duchies of Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily to a kingdom. Roger’s son and successor became its first ruler, King Roger II of Sicily.

The new kingdom was the richest and most advanced state of western Europe. In part, this was because it took full advantage of the talents of its Muslim population, which skilled tradesmen, merchants, and scholars. Whatever the pope’s religious motives behind granting the Normans the right to conquer Muslim Sicily, they cared most of all about power. As such, they happily patronized Arabs, Greeks, and Jews alike.

An exaggerated and somewhat fanciful picture is often painted of the tolerance and openness of Moorish Spain. Norman Sicily probably came much closer to this rosy portrait. Muslims, Jews, and Byzantine Christians were all allowed a dignity and freedom of worship unheard of elsewhere in either Christian or Islamic lands. Indeed, they were treated with more than just haughty indifference; men of merit were held in high esteem, whatever their religion. Talented Greeks and Arabs were given high positions as administrators, and craftsmen of all faiths were employed by the court.

But it should be understood that the tolerance of Norman Sicily was quite a different thing from the very recent and peculiar modern notion of tolerance. Members of different groups largely stuck to their own. Norman governance concerned itself with taxation, military affairs, and justice, but various peoples were free to maintain separate customs and govern themselves at the communal level.

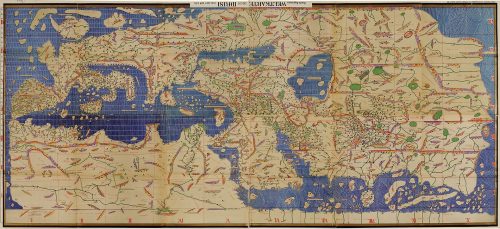

Only at court, where the patronage of a wealthy elite brought many different people together, was there a true blending of cultures. The result, however, was an astonishing amalgamation of wildly different styles: architects ornamented northern Gothic buildings with Arab designs, while Greek artists decorated the interiors with Byzantine mosaics. Nor was this fusion a strictly monumental phenomenon: the Tabula Rogeriana, a world atlas composed by an Arab geographer for Roger II, was produced as a bilingual Arabic-Latin text.

The Sicilian court attracted scholars from as far afield as England and Baghdad, who then brought bits of its unique culture back to their homelands. This cultural exchange was much more than an accident of circumstance—the Norman kings took an active interest in the culture of the island, and several learned Arabic, Greek, and Sicilian. As late as 1250, the king of Sicily was fluent in all three languages.

But by that time, the period of tolerance was over. Human nature had reasserted itself, and the close-packed cultures of the island had broken out into conflict. In 1224, Islamic insurrections compelled the authorities to expel all Muslims from the island. Thus ended the living legacy of Muslim Sicily, even as its cultural legacy survived.

The Effaced Legacy of the Greeks

One side-effect of the Norman reconquista was the gradual disappearance of Greek culture on the island. Southern Italy and Sicily had long maintained a Greek character, as far back as the first Euboean colonies of the 8th century BC. This had persisted under Roman rule, and was revitalized by later Byzantine reconquests.

As long as Byzantium maintained a presence in Italy, Greek communities were culturally sustained, even under Muslim rule. But the Normans expelled the last Byzantine garrison from Apulia in 1071, the same year as the siege of Palermo, and never again would a Greek power rule any part of Italy.

The kingdom founded by the Normans would be enduring, lasting well into the 19th century. But while the court was influenced by and patronized Byzantine high culture, the long-term trend of its institutions was towards Latinization. Over time, the Roman Church replaced Greek clergymen with Latins, and the Sicilian-speaking majority asserted its cultural power.

The Ongoing Reconquista

The great irony of Norman Sicily is that the birth of such such a remarkable kingdom kick-started a self-consciously religious struggle against Islam. Christians in Spain began conquering in the name of God. Pisa and Genoa, long harried by pirates from Muslim Sicily and elsewhere, sacked the capital of Ifriqiya in 1087.

Knights in Normandy and England kept up contact with relatives fighting down south. When the First Crusade was preached in 1095, the duke of Normandy and many other nobles took the cross, inspired by their cousins’ example.

Within forty years of the Normans gaining a toehold in Muslim Sicily, Toledo and Jerusalem were back in Christian hands. Christian princes on both sides of the Mediterranean were aggressively expanding their domains, and everywhere Islam was in retreat. The Sicilian Reconquista was a precursor to these titanic clashes—itself not a holy war, but the opening act to the great crusading era.