A recent study by academics at Oxford and elsewhere has concluded that grisly stories of ancient Phoenician child sacrifice were true:

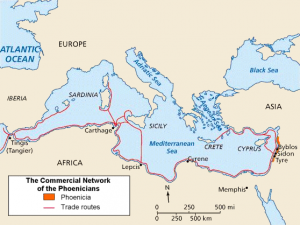

Children – both male and female, and mostly a few weeks old – were sacrificed by the Carthaginians at locations known as tophets. The practice was also carried out by their neighbours at other Phoenician colonies in Sicily, Sardinia and Malta. Dedications from the children’s parents to the gods are inscribed on slabs of stone above their cremated remains, ending with the explanation that the god or gods concerned had ‘heard my voice and blessed me’.

As with any truly strange custom in antiquity, it is hard to believe that people were really like that.

On the other hand, it is not so strange given what else we know about ancient peoples. The Spartans, a people as different from us as any, abandoned unhealthy babies on mountainsides. And the Bible mentions the Tophet, a place near Jerusalem where straying Israelites burned their children in sacrifice to Moloch and Baal, in accordance with the ancient Canaanite religion.

The Israelites and Canaanites were close neighbors to the Phoenicians, and their languages, customs, and religions share deep roots. The biblical story of the Tophet therefore seemed to corroborate Greek and Roman accounts of child sacrifice in the region. Archaeologists started using the word “tophet” for child cemeteries discovered in ancient Carthage and other Punic colonies, which were presumed to be the sites described by ancient authors.

Indeed, it was only recently that stories of Phoenician child sacrifice were disbelieved:

In the 20th century, people increasingly took the view that this was racist propaganda on the part of the Greeks and Romans against their political enemy, and that Carthage should be saved from this terrible slander.

This was the age of decolonization, when all non-Western people were seen as inevitable victims of imperialism.

But perhaps stories of child sacrifice were rejected because the Phoenicians are otherwise so agreeable to modern sensibilities: they were cosmopolitan, enterprising, and literate (they invented the precursor to our alphabet), and they were great explorers (the rather more positive claim that they circumnavigated Africa is now generally believed).

The story, as it now appears, shows us that we can never assume ancient people thought or behaved like us. Whatever the passing similarities, the past is truly a foreign country.