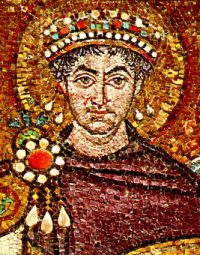

The Late Antique Folklore blog has a post on Byzantine legends from the sea. The tales are from Procopius, a 6th-century court official in Constantinople who served under Justinian, and is the most important source for the period. Procopius liberally sprinkled his writings with anecdotes and observations, two of which LAF recounts. The first is a story of a whale that terrorizes ships around Constantinople for decades, until it finally beaches itself by accident. The second is a discussion of the legendary magnetic mountain, said to be an island in the Indian Ocean, that pulled the iron nails out of ships, explaining why ships there did not use metal.

Other than the intrinsic appeal of the stories, they are interesting for the echoes of them that appear in later sources. These echoes show up in one very interesting set of sources in particular: the Arabian Nights.

Old Sea, New Sailors

It should be no surprise that the Arabs inherited many myths and fairy tales from the Byzantines, especially relating to the sea. The coasts of the Eastern Mediterranean were largely Greek-speaking, and Greeks dominated shipping in those parts up until the Arab conquests—indeed, they manned early Muslim fleets. Along with such utilitarian skills, the Arabs also inherited Greek science and literature from their conquests, and the caliphal courts at Damascus and Baghdad made prodigious efforts to translate and publish these works in Arabic. Thus by avenues high and low, Greek legend entered the body of Arabian folklore.

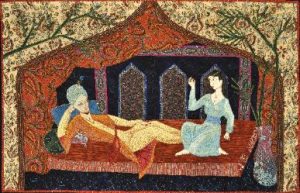

Back to Procopius: the two stories mentioned in the Late Antique Folklore post, about a deadly whale and a magnetic mountain, are similar to stories from Sinbad the Sailor and the Thousand and One Nights, respectively. The Thousand and One Nights, or Arabian Nights, were a collection of tales formed from a core of originally Persian stories. Over time, they accreted Indian, Arabic, and possibly even Chinese additions, growing into the mass of legends, fables, and tall tales we know today.

The Orient Looks East

The Voyages of Sinbad, which were only added to the Nights by European editors, have a much more definitely Arab origin. They are set in a specific time and place, Iraq under the Abbasid Caliphate, in the mercantile setting of Basra. Basra was then, as now, Iraq’s sole port on the Persian Gulf. Commerce in that part of the Arab world was oriented toward the Indian Ocean; unlike the seafaring traditions in Syria and Egypt, it was not at all inherited from the Greeks, but rather from pre-Islamic Arabs and Persians.

The Sinbad stories have a similar narrative frame to the Nights, involving the hero recounting his stories. Every day he tells of a different adventure, each one following the same arc: he gets restless, goes out to sea, has a misadventure, then returns home to enjoy his wealth in peace, seven times in all before retiring for good. On his first voyage, his ship was destroyed when it landed on an island that turned out to be an enormous whale. Stories of whales or other sea monsters attacking ships are certainly not unique, and go back as far as the Biblical story of Jonah. Nevertheless, Sinbad’s tale represents a continuation of this tradition, from ancient times through Procopius.

The Attraction of the Past

More specific echoes of Procopius are found in the Thousand and One Nights. In the Third Kalandar’s Tale, a magnetic mountain pulls the iron nails out of passing ships and causes them to fall apart. This seems to be lifted directly from the older Greek story.

This appearance in an Arab context is interesting. The Greeks had used the legend of magnetic mountain in the Indian Ocean to explain why ships there did not use iron nails. The traditional style of ship in that part of the world, called dhows, were constructed by sewing planks together. These continued to predominate up until the Portuguese arrived in the 15th century, when the need to carry cannons forced sailors to adopt sturdier ships.

It was not ignorance (or magnetic mountains) that explained the lack of nailed ships in the Indian Ocean. An 8th-century viceroy of Iraq had in fact tried to introduce them there, but could not get sailors to adopt them. The shallow waters and sandbars of the Persian Gulf and Red Sea caused ships to frequently run aground, and the more loosely-joined sewn ships absorbed the impacts better. It is strange, then, that the Kalandar of the story, a companion of the caliph in Baghdad, would mention ships made with iron nails.

Context, as always, is key to understanding this. For one, the stories in the Nights are highly fantastical, and give little faithful description of the lands they mention. For another, the stories seem to have been mostly told in a Mediterranean milieu. Surviving manuscripts of the Thousand and One Nights come from Syria and Egypt, where nailed ships were used. It is unsurprising, then, that these stories are similar to older Greek legends: Mediterranean people imagining what the Indian Ocean was like.

Thus the light of Greek influence reveals much about Arabic folklore by the shadows it cast, the details about the far side that should be there but aren’t; Persian, Egyptian, and Indian influences cast similar lights. The arrival of the Arabs on the world stage came so suddenly that we often get a perfect snapshot of what influenced them just by looking around. No matter where a person is in the world, there is always an East and a West.

Read more:

The Secret History (Penguin Classics)

Procopius’ salacious history of anecdotes, gossip, and his own unvarnished opinion of the prominent figures of the day. Includes the stories of the deadly whale and the magnetic mountain.

The Arabian Nights (New Deluxe Edition)

This version is translated from the earliest complete, extant text, the 14th-c. Mahdi edition.

Tales from the Thousand and One Nights (Penguin Classics)

This is a collection of popular stories from the Nights, including later additions such as Sinbad and Aladdin.