An exciting new discovery has been made in England. A man tromping through his fields stumbled into a rabbit hole that concealed a secret. The hole was in fact a narrow tunnel leading to a door. Behind it was a small series of caves, hollowed out by the medieval military order called the Templars. This order was created to ensure the safety of Christian pilgrims in the Holy Land, and was devoted to fighting the infidel. Outside of the Holy Land, they possessed countless chapter houses all across Europe, where fighting men were recruited, trained, and indoctrinated.

So what was this Templar tunnel, then? The underground chambers appear to be a chapel of some sort, though not of typical Christian design. The not-quite-orthodox layout calls to mind rumors of pagan ceremonies that swirled around the order at the time of its dissolution. The origin of those stories is tied up with the order’s great wealth; to understand the purpose of the Templar tunnel, it is first necessary to go back to their role as the first bankers in Europe.

Early Bankers

During the Middle Ages, travel across the Mediterranean was perilous. Storms, shipwreck, and piracy threatened sea-goers, making the transport of silver especially hard. This was a tough problem for Christians making expensive pilgrimages to Jerusalem, so the Templars developed a rudimentary banking system. Pilgrims would deposit money at Templar chapter houses in Europe in exchange for a bills that would let them withdraw the same amount, minus a fee, from chapters in the Holy Land.

This, along with large donations from pious magnates, made the order fantastically wealthy. Even after the Crusaders’ expulsion from the Holy Land, the Templars’ banking network made them a political force to rival the monarchs of Europe—and their wealth made them an attractive target.

Suppression of the Order

In 1307, Philip IV of France went after the Templars. He had already expelled both Jewish and Lombard bankers from his realm, seizing their assets in the process. His profligate spending had put him deeply into debt, and he was always in search of new sources of revenue; Templar silver promised just that.

On Friday the 13th of October, hundreds of Templars were arrested across France, followed by waves of arrests throughout Europe. Over the next several years, the imprisoned knights were tortured and forced to confess to their alleged crimes: heresy, idol worship, sodomy, and more.

Despite papal efforts to ensure due process, Philip had dozens of Templars abruptly burned at the stake in 1310. This cowed the order’s would-be defenders, allowing Philip to persuade the Pope to dissolve the order and transfer its property to the Hospitallers, another military order. In the course of this transfer, royal agents ensured much of this property ended up in the hands of the crown and its allies.

For centuries after the trial, strange stories were whispered about the Templars. Some maintained that a small number escaped Philip’s clutches with their treasure, founding another order to serve their original mission. Others maintained that they had indeed practiced some sort of occult magic, which their surviving followers continued. So what does this tell us about the recently-discovered Templar tunnel?

As it happens…

….nothing. The story is false, a sensationalized concoction designed (successfully) to attract media attention. The caves are likely from the 18th or 19th century, an example of what was called a folly. Landowners would make imitation Greek or Roman temples, Egyptian pyramids, or Gothic ruins to ornament their property. Some would even charge admission to tourists.

More interesting is a real Templar tunnel, which played a significant role in history. It was was discovered 20 years ago in Akko, Israel, better known as the city of Acre. But to understand their importance, it is necessary to go back to the end of the Crusades.

The Fall of the Crusader Kingdom

Following Saladin’s reconquest of Jerusalem in 1187, the Crusader states lived in constant peril. The Kingdom of Jerusalem was now confined to just a few coastal cities, with the great port of Acre as its new capital.

Possession of good harbors was the barest of necessities for Western Europeans’ survival in the Holy Land. Genoese, Venetian, and Pisan galleys carried out a lucrative trade, ferrying men and supplies from Europe, and the luxuries of the East back the other way.

But without control of the hinterlands, the Christians had no buffer against Muslim armies. Recently united, Syria and Egypt furnished enough manpower to overwhelm the weakened kingdom. Bit by bit, Islamic forces ate away at the remaining Frankish territories, until only a few possessions remained.

Finishing Blow

In 1291, Sultan al-Ashraf Khalil descended on Acre to remove the last remaining Christian toeholds. His army enveloped the city, and began preparations for the siege. Panicked citizens sent as many of the women, children, sick, and elderly as they could by galley to Cyprus, where the titular King of Jerusalem held his court. The galleys then promptly turned around to aid in the defense of the city, where they would play an important role.

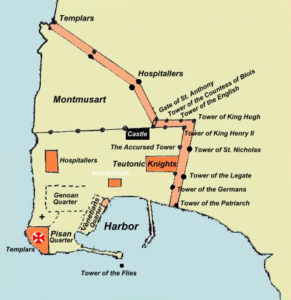

The Latins put up a heroic resistance. Where before petty jealousies had divided them—the military orders, the Italian maritime republics, dispossessed Crusader barons all squabbling among themselves—the Christians now fought as one in a last, desperate struggle. Each faction was given a sector of the walls and several walls to defend, with Venetian and Pisan ships protecting the seaward side of the city.

The sultan was a patient man, and did not waste his men on fruitless assaults against the walls. His sappers dug tunnels from the siege camp to each of the towers in the city walls, undermining them one by one.

The final assault came on May 18th. Though the Crusaders resisted throughout the day, a sizable contingent fled by ship after nightfall. Seeing the vacant walls at daybreak, Khalil ordered a concentration of effort on the vulnerable sector.

Defenders swarmed to the breach; the rest of the city panicked. The remaining women and children swarmed to the wharves, where some galleys remained. Desperate ladies offered their jewels and their bodies for safe passage.

Masses of Muslim soldiers had now forced themselves inside the city, stabbing down the main arteries in a gruesome slaughter. The streets were a killing zone—all caught in the crush could only pray, and await their fate. The lucky ones were taken as prisoner; the foresighted had taken refuge in the Templar’s citadel, located in the southwest corner of the city. Before long, those holed up inside were the last remaining Franks in the city, and the fortress was enveloped by Khalil’s forces.

After a protracted parley to negotiate safe passage for the warriors and civilians trapped within, talks broke down. Khalil ordered his men to storm the citadel, which had already been undermined by his sappers. Such was the weight of the attacking force that the entire structure collapsed, killing everyone inside. Thus perished the last Christians in Acre.

Opportunity Lost

So what does all this have to do with a Templar tunnel? That is the part missing from the story of Acre’s fall. But first, back to modern times.

703 years after the siege, a woman in modern Akko called the utilities company to complain about blocked sewage. In the course of investigating, city authorities discovered an underground passageway, filled with the dreck and sludge of centuries. Archaeologists took over the exploration of this mysterious corridor, and found that it stretched a quarter-mile, from the wrecked citadel to the harbor.

The passage likely served as a protected way to unload cargo—including banking deposits—from ship to safety. City streets in the Levant were not safe, even to the high nobility (years before, a king of Jerusalem had been murdered in the streets of Tyre). Moving so much valuable cargo as they were, the concealed corridor allowed the Templars to move gold and provisions in safety—and secrecy.

The chroniclers were quite explicit that the Templars and their charges were trapped in the fortress—there was no hope for escape save through a truce with the sultan. A picture emerges: the Muslim army had swept down to the port, sealing it off to anyone trying to escape through the tunnel. It is unlikely that any ships remained in the harbor anyway.

The Templar tunnel in Acre is more prosaic than the recently discovered one in England, which only feeds the fervid imaginations of the occult-minded. It played an understated, if important, role in the order’s operations in the Holy Land. It is interesting in that it highlights two of their key roles: securing the cash of crusading knights, and securing the cities they had captured. But against the forces arrayed against the Christians, even the Templars’ valiant struggle was futile.

Want to Learn More? Read:

The Templars: The Rise and Spectacular Fall of God’s Holy Warriors