The beginnings were inauspicious. A middle-aged man, accompanied by a paltry group of followers, sought refuge from the hounds of their oppressors in a remote mountain fastness. For decades, their people had been persecuted by one of the most powerful empires the world had ever seen—the Seljuk Turks.

The wretched group found themselves before the imposing fortress of Alamut, high up in the Alborz Mountains. This mountain chain towers over the Iranian plateau, a sanctuary from the palaces and cities teeming with intrigue far below. From here, the refugees would soon make a name for themselves as the hashishin, or hashish-eaters, which would come down to us as “assassin.” These original Assassins would strike fear in the hearts of rulers all across Asia.

Ismaili Background

The man who led this woeful lot was named Hassan-i-Sabbah. He was born into a Persian Shi’ite family, and converted to the Ismaili sect in his youth. Like all Shi’ites, the Ismaili believed that the rightful spiritual leaders of Islam, known as imams, descended from the prophet’s cousin and son-in-law Ali.

Different Shia sects disagreed over the chain of succession further down the line, with Ismailis particularly revering the seventh imam, Ismail ibn Jafar. This put them at odds with the majority of Shi’ites, making them a minority within a minority.

All Shi’ites were at odds with the Sunni majority, however, which believed that spiritual authority had properly passed through a series of caliphs, ruling first from Damascus and later from Baghdad. Caliphs were supposed to hold both spiritual as well as temporal authority, although they had lost their secular power to the Turks who were then ruling Sunni lands.

These Seljuks, erupting out of their Central Asian heartland, had conquered all of Persia, Iraq, Syria, and much of Byzantine Anatolia. They paid lip-service to the caliph, and legitimized their religious credentials by leading occasional persecutions of the Shi’ites.

At the time, Ismailism was the official doctrine of the Fatimids ruling Egypt, chief rivals to the Seljuk Turks. Cairo was a major center of Ismaili scholarship, and Hassan’s mentor encouraged him to go study there. Hassan had already made a name for himself in Persia, gaining a high position in the Ismaili missionary organization—he was full of promise.

After extensive travels to various Ismaili communities throughout the Seljuk domain, where he met with scholars, religious figures, and community leaders, Hassan finally arrived in Egypt. He spent three years studying there, before fate turned against him. Another split was developing within Islam around this time, and Hassan found himself aligned with the emerging Nizari branch of Ismailism. This put him at odds with certain powerful figures in Egypt, and he was forced to flee.

Returning home to Persia, Hassan was appointed chief missionary to the northern region of Persia that stretched from the Alborz Mountains to the Caspian Sea. He was highly effective, building up a fervent, devoted following among the locals. It would serve him well for what was coming next.

The Eagle’s Nest

When Hassan arrived at Alamut in 1090, he was bearing a disguise and false name. His missionary activity had angered the Seljuk grand vizier, Nizam al-Mulk, who had recently issued an arrest order for him. Luckily, the unsuspecting lord of Alamut took him. And then, just as abruptly, the master of the castle was turned out by his own men.

What had happened? It was a masterstroke of Assassin trickery, that would characterize their operations for centuries to come.

Hassan had long before identified Alamut as an ideal headquarters for his movement. It was distant from Seljuk centers of power, secure, and able to sustain itself. Most important of all, it overlooked several villages of devoted Ismailis that Hassan had built up over the past few years. But his own forces were small and weak, and could never hope to take the fortress in a head-on assault.

Instead, using patience and foresight, he set his fanatical followers to work infiltrating Alamut. They acquired positions all through the castle, as soldiers and servants alike. When Hassan arrived, he merely had to give the word for them to deliver Alamut to him.

Ruses of this sort would become Hassan’s trademark: planning months or years ahead to infiltrate a small group of ferociously devoted followers—his fedayeen, or “those who sacrifice themselves”—into a target’s inner circles, then delivering a devastating blow at just the right moment.

Fear-tinged stories began to swirl about this clever and ruthless “Old Man of the Mountain” who ruled from Alamut—”Eagle’s Nest” in Persian. Like an eagle, he would swoop down from on high to strike his unsuspecting prey. His core group of fedayeen would soon come to be known as the Assassins—the original assassins, whose techniques terrorized their enemies and inspired legends.

Guardian of the Ismailis

With a secure base of operations, Hassan’s fedayeen fanned out across the Seljuk realm. Meeting in secret with other Ismailis, they organized a self-defense network. The extensive contacts Hassan had formed within the Nizari Ismaili community doubtlessly paved the way for his followers. Wherever they found fellow Ismailis, they were given a warm welcome and provided with extensive local knowledge.

Bands of fedayeen seized more castles and strongholds throughout Persia and Syria. They would scout out suitable locations in areas near existing Ismaili communities, then capture, purchase, or build from scratch a fortress.

Scrupulous care went into selecting sites: Each fortress had to be far enough away from major centers to discourage attack. Fortresses also had to be within striking distance of one another—the Assassins were always small in number, and needed to be able to reinforce quickly.

Being self-sufficient, the Assassins required adequate sources of wood and stone in the neighborhood, with which they could effect any necessary repairs, as well as sufficient water and agricultural land nearby so that the fighters could sustain themselves in the event of a siege.

With such characteristic diligence, Hassan’s disciples erected a defensive chain of fortresses in the Alborz Mountains of northern Persia and the Nusayriah Mountains of the Syrian coast. In Syria, the great fortress of Masyaf assumed the same role as Alamut, a de facto regional capital. In the future, it would occasionally supersede the original capital in terms of importance.

But for the span of Hassan’s life, all strings would be pulled by him alone. He had effectively created a state for himself. His territory was small, and lay dispersed within the bounds of a great empire, but he nevertheless ruled as its unquestioned sovereign.

The Original Assassins Earn Their Name

Having turned two mountain ranges into effective fortresses, having networked the disparate Ismailis into a coherent bunch, and having the fanatical devotion of several thousands of men, the Nizaris began to assume more than a purely defensive character. If they were to protect the members of their faith, they would have to strike hard against their enemies.

At that time, the Nizaris had no greater enemy than Nizam al-Mulk—the same grand vizier who had earlier ordered Hassan’s arrest. Main advisor to two Seljuk sultans and enforcer of Sunni orthodoxy, he was a power unto himself.

A man dressed as a Sufi dervish rushed the vizier and stabbed him to death. The vizier’s bodyguards killed this original assassin before he could be questioned, but it was widely believed to be one of Hassan’s fedayeen. Soon after, the Seljuk sultan himself died in questionable circumstances. Some believed the caliph in Baghdad had him poisoned, while others blamed the late al-Mulk’s allies.

Whatever the truth, the Seljuk Empire was plunged into chaos. The sultan’s descendants went to war with one other, establishing independent states for themselves in Anatolia, Syria, Iraq, and Persia. For a time at least, the Ismaili community was delivered from its oppressors.

After a few decades, however, they faced a new threat. Sultan Sanjar had managed to reunite large parts of Seljuk territory, and was consolidating his power. In 1126, he sent a formidable host to subjugate the recalcitrant Ismailis at last.

While on his way to besiege an Assassin fortress, Sanjar awoke one day with a dagger lying beside his pillow. Underneath it was a note from Hassan, saying he hoped for peace. The message was clear: the Assassins could have easily killed the sultan, but were willing to forego a bloody war.

Sanjar was duly spooked. As a man with many enemies, and whose own father had been assassinated, he decided it was wiser to withdraw his forces. The sultan made the Nizari’s de facto independence formal.

This would be a template for future Assassin operations: whenever a powerful outsider threatened them, they would send their spies and infiltrators to work, getting key enablers in place throughout the enemy organization. At the perfectly-judged moment, they would strike, either eliminating a key official or by performing some gesture that would instill a healthy dose of fear, but keep short of anything that would provoke a fight to the death that they could not win.

When the powerful Saladin was completing his conquest of Syria, he attempted to reduce the Assassin strongholds there. His adversaries used the same trick: a poisoned dagger, a note, and several hot biscuits were left by his bed. The message was received.

These original Assassins, with a pragmatism born of weakness, sought the most economical means to achieve their goals. They preferred cooperation to threats, threats to assassination, and assassination to outright warfare. Only in drastic circumstances, such as the siege of Girdkuh in 1253, would they fight a conventional battle.

A Cloud of Legends

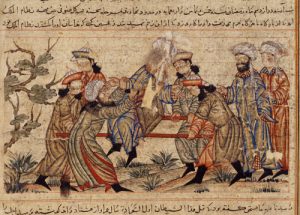

A haze of myths, fantastical stories, and rumors began to float around these original assassins. Like a cloud of hashish smoke, it obscured their true nature and induced delusional paranoia in their enemies. No one knew much about these fearless killers, who seemed to hold occult beliefs, and were able to insinuate themselves everywhere.

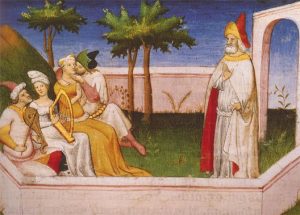

Marco Polo recounted that Hassan would feed his fedayeen hashish, then take them to the splendid, hidden gardens on the castle grounds. There they would be entertained by beautiful girls claiming to be the houris of Paradise—indeed, they were in Paradise, to which the Old Man alone could deliver them. With such a promise, the fedayeen became totally loyal, willing to do anything for him. This distinguishing use of hashish was what gave the original Assassins their name—hashishin transformed into assassin.

The esoteric beliefs of the original Assassins contributed to such legends. Nizari doctrine was obscure, and only fully revealed to the initiated. Many doubtlessly feared that they held some secret power. The mystery of it only contributed to their reputation.

But it was the Assassins’ fanatical loyalty that was most terrifying. Legend told that while entertaining a visitor, the one commander ordered two of his fedayeen to kill themselves. Without hesitation, one stabbed himself and the other flung himself off a high tower. They were so confident in the rewards of Paradise that they eagerly embraced death. This fearlessness was not just a display to intimidate visitors: it allowed the Assassins to carry out murders with steel nerves. One of their most terrifying trademarks was how calmly Assassins awaited torture and death after a successful kill.

The motives of the Assassins were not always so easy to discern, either. In 1192, King Conrad of Jerusalem was struck down in the streets of Acre by an Assassin. Why? Had Conrad angered the Assassins? Or had his political enemies merely hired one of them? Had these fearless zealots of their faith turned mercenary? Rumors swirled in an environment thick with fear.

Which suited the Assassins just fine. They only spoke through actions, not words. If would-be enemies became paralyzed trying to decipher them, so much the better.

The Mongol Steamroller Flattens All

The Assassins finally met their fate with the arrival of the Mongols. The conquerors from the east cared little about squabbles among religious sects, but they did demand absolute obedience. The Assassins, long accustomed to independence and perhaps too convinced of their own invincibility, refused to submit.

At last, they met a foe they could not intimidate. For one thing, the Mongol hierarchy did not lend itself to infiltration. Khans secluded themselves from society at large, only allowing members of the royal household into their presence. The Assassins tried and failed to kill the Mongol commander, which only angered him.

Mongol armies quickly stormed several fortresses in eastern Persia. Several more were able to hold out for a few years, but time was against them. The Mongols finally compelled the Assassin commander to surrender himself from his fortress of Maymundiz. He wrote messages to the seneschals of all other Assassin fortresses, ordering them to surrender.

The Assassins held on a little while longer in Syria, but their territories were soon annexed by the powerful Sultan Baybars, the scourge of Crusaders and Mongols alike. Local Ismaili commanders were sometimes allowed to keep their castles as vassals of the sultan, and were occasionally hired out to kill Baybars’ political enemies. The true, original Assassins were now just common assassins.

So Who Were these Original Assassins?

The original assassins were able to accomplish much with very little. Over 300 years, they are estimated to have murdered only a few dozen people. Yet their targets were so carefully chosen, that even the mightiest kingdoms and empires feared them. Careful preparation, fanatical dedication to the mission, and above all a keen understanding of human psychology gave their sect force far beyond its numbers.

What was it that motivated them, then? First and foremost, they wanted to protect and defend the Ismaili communities. They never showed any desire for conquest or domination. While nobody knows for sure what messianic visions the Assassin leaders had for their people, they were generally content to live in peace with anyone who left them alone.

And they were successful in that. Those parts of Syria and Persia where they operated today have large numbers of Ismailis. But they were better known for the methods they used. It is no surprise that the original Assassins gave their name to the profession they practiced so well.