William Dalrymple reviews a harrowing account of the race to save Timbuktu’s ancient manuscripts during Al-Qaeda’s takeover of the city in 2012:

The realisation that Timbuktu’s fragile heritage was in danger set off alarm bells across the world. The city was once one of Africa’s most revered centres of learning and the arts. From the 13th century onwards, but particularly during the great days of the Songhai empire, which reached its peak during the 15th and 16th centuries, Timbuktu became the West African equivalent of Oxbridge or the Ivy League, pullulating with scholars busy copying out old Arabic manuscripts and composing new works of theology, history and science [….]

One librarian claimed to have organised a small army of smugglers lining the route to Bamako, who carried hundreds of thousands of manuscripts out on convoys of lorries and later, as the French Foreign Legion moved north to take on al-Qaida, in fleets of small river boats down the Niger, braving pirates, ambushes, corrupt government troops and trigger-happy French helicopter patrols. Of these stories English grew to be profoundly sceptical. He acknowledges that some manuscripts were indeed saved in actions that “undoubtedly took chutzpah and courage, from the directors of the libraries as well as more junior colleagues, who braved the jihadists’ sharia punishments”.

Whatever the truth to these stories, a number of manuscripts were destroyed, as were many more saved. For a brief moment, this desperate episode focused the world’s attention on Timbuktu’s patrimony, and highlighted how important this dusty backwater had once been. The city was at one time the center of learning for all West Africa, and attracted scholars from great distances. The story of its rise is strangely similar to that of an earlier Islamic center: Baghdad under the Abbasids.

Golden Empire

Timbuktu first rose to prominence in the 14th century. Lying on the upper Niger River, it had long been a market town where Saharan nomads traded with merchants from the Nigerian delta. Its name would only become known to the world after being absorbed into the Mali Empire.

When Mali annexed Timbuktu in 1325, the empire had been expanding across the western Sahel for the past century. Mali financed its conquests with profits from abundant deposits of gold and salt, which made its rulers fantastically wealthy. In one famous episode, when Musa I of Mali made the pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324, he distributed gold so liberally along the way that its value in Cairo dropped by a quarter. This incredible wealth allowed the empire to solidify its control over the trans-Saharan trade routes, creating a virtuous cycle of enrichment and expansion.

Timbuktu was acquired by that same Musa on his return from Mecca. He had brought back many scholars, jurists, and architects from his extravagant expedition and settled them in the cities of his empire. Those settled in Timbuktu were chiefly employed at the Sankore Mosque,which sponsored a madrasa (Islamic school) that was already held in high esteem by Muslims of the region. This, along with a generous endowment to the madrasa, would be Musa’s most important contribution to Timbuktu’s eventual fame. He single-handedly created a scholarly community that tied West Africa into the greater Islamic world.

Apogee

Even as the Mali Empire weakened and fell, Timbuktu continued to flourish. A century after Musa acquired the city, it was seized by the Tuareg, a confederacy of Berber nomads that occupied the Sahara and Sahel. The Tuareg were great traders, regularly traveling the vast distance between the Moroccan coast and the upper Niger River. Commerce subsequently flourished and Timbuktu’s reputation grew.

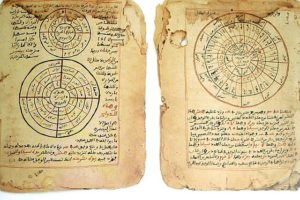

Several decades later the city was acquired by Songhai, another expanding empire of the western Sahel. At its height, the Songhai Empire was richer and larger than Mali had ever been, controlling desert outposts all the way up to the border of modern Morocco. It was during this time that Timbuktu reached its cultural apogee. The Sankore Madrasa, along with two other mosques in the city, formed a network of scholars that attracted pupils from far away. There was an active production of manuscripts, ranging in subject from Islamic law to mathematics to astronomy and geography.

Decline and Legacy

Timbuktu underwent another change of hands in 1591 when it was conquered by the sultan of Morocco. This time the consequences for the city would be more serious: scholars at the madrasas were seen as a political threat, and many of them were sent into exile. Lasting though Timbuktu’s reputation would, the living community of men of letters was gone forever

Just as the city’s intellectual production had earned Timbuktu a reputation in the Islamic world, its enormous gold trade brought it to the attention of European maritime powers. Its name made its way onto maps, geographies, and legendary accounts. The city was so inaccessible that fantastic myths swirled around it, compelling brave travelers to seek it out. It was not until 1828 that Frenchman René Caillié became the first Westerner to return home with a credible account of visiting the city. What he found was a small, impoverished town of no importance. The glory days of Timbuktu were far in the past.

Echoes of Another Lost Empire

Obscure settlement, to glorious center of learning under great empire, back into a provincial backwater—such was the arc of Timbuktu’s history. Another city followed this trajectory with remarkable similarity: Baghdad under the Abbasids.

Baghdad began as a small village on the Tigris River, and was turned into the capital of the Islamic world in 762. There, the Abbasid caliphs commissioned the House of Wisdom, a library dedicated to compiling and translating all the world’s knowledge. In similar manner to what Musa I would later do, the caliphs used generous patronage to bring in Persian, Greek, Syrian, and Egyptian scholars, essentially creating an intellectual community out of thin air. This community lasted long after the city had waned in political importance.

Baghdad’s fate was grislier than Timbuktu’s, but the result was the same. The Mongols sacked the city in 1258, leaving the Tigris running black with ink from the books thrown in. Like the intellectual purges following the Moroccan conquest of Songhai, the sack effectively ended Baghdad’s time as a center of learning. From then until the founding of modern Iraq, the city was just a small provincial capital.

The parallels extend even to the present: the looting of Iraq’s antiquities following the US invasion of 2003 was mirrored by Al-Qaeda’s destructiveness in 2012. For all the efforts to preserve treasures from the past, catastrophe always looms. Antiquities that survive today are but the faded relics of living, breathing civilizations, as subject to degradation by the elements as to their willful destruction by man. And it is as fragile testaments to the glories of the past that they have such value.

Want to learn more?

The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu: The story of how Timbuktu’s ancient manuscripts were saved from invading Al-Qaeda forces.

The House of Wisdom: How the Arabs Transformed Western Civilization: More about the Baghdad at the peak of its intellectual brilliance.